Some women are moved across the country. Others are lured by traffickers at school. Many of them know the perpetrators who keep them isolated and dependent on them

JANICE DICKSON – Globe and Mail

PUBLISHED FEBRUARY 22, 2021

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/H7UYLWXCNZDZRHCA2BQCROKFDU.jpg)

GALIT RODAN AND DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

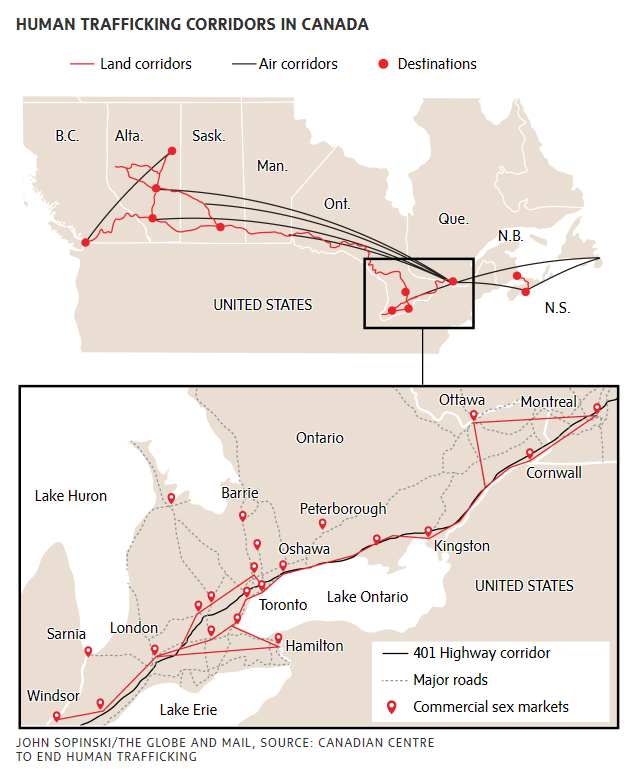

Sex traffickers are using the country’s major highway networks to transport women and girls, taking them to small towns and cities in order to isolate them, avoid police and maximize their financial gain, according to the first research in Canada analyzing how victims are moved.

A report from the Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking identifies some of the key routes traffickers use to transport their victims, isolating them from family, friends and familiar surroundings that could offer an eventual escape, and making them wholly dependent on their perpetrators. The constant movement also allows criminals to avoid detection by law enforcement and gives them access to more profitable markets.

The research suggests there’s a trend in young women being trafficked from Quebec to Alberta, where criminals can make more money selling sex services than in other provinces, according to police officers.

And sex trafficking is so prevalent across Canada that it occurs wherever “there is a highway and access to the internet,” the report says.

“I think too many people believe that this is an issue that happens in other countries or that it’s an issue of kidnapping and abduction,” says Julia Drydyk, the centre’s executive director. “And, really, it’s far more commonplace.”

To compile the report, the centre reviewed academic reports and media coverage, and interviewed police officers and service providers to determine its findings. Most of the victims are women and girls, but the report notes a small number of respondents worked with male or trans-identified survivors. Interviewees said most victims and survivors they encountered were between the ages of 18 to 24, but ranged from 12 to 50.

In Alberta, shuttling victims between Calgary, Edmonton, Fort McMurray and Grande Prairie allows sex traffickers to find plenty of willing customers near oil patch work camps, and exploit the province’s online sex markets, too.

“A growing trend in this corridor is the number of victims and survivors from Quebec who speak little to no English,” according to the report. “Not only do language barriers serve as another method of control, but it is also believed that sex buyers see women from Quebec as exotic and novel.”

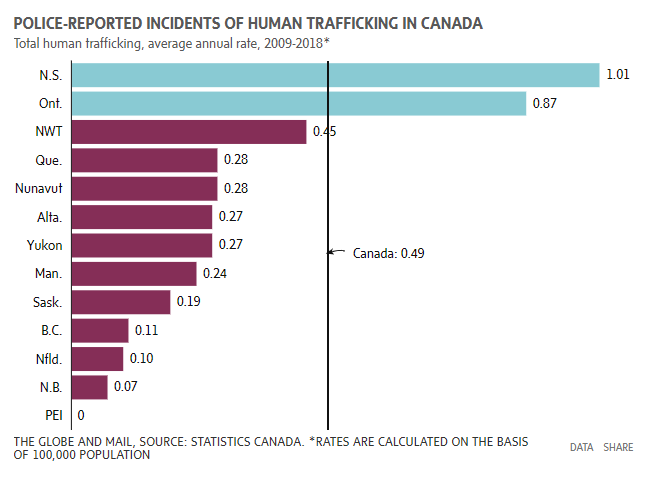

Another well-worn route has perpetrators taking victims from Halifax to Moncton. Corporal David Lane, the RCMP’s human-trafficking co-ordinator in Nova Scotia, says the province is well known in the criminal and policing world for exporting victims of human trafficking. (Data published by Statistics Canada in June shows that Nova Scotia and Ontario have higher rates of human trafficking than the national average, citing figures from 2009 to 2018.) Some target women and girls from Nova Scotia because they can sell them the idea of giving them a better life, he said.

“If you’re from a rural fishing village in Nova Scotia, and someone offers you to go to live next to the Air Canada Centre in Toronto, to go to Calgary or Vancouver, it would probably be pretty lucrative,” Cpl. Lane says, “especially when you thought they were someone you loved.” That appears to be a common thread among trafficking victims, according to the report: They often know their abusers. It might even be someone they loved or trusted, such as a boyfriend, a family member or friend.

Detective-Sergeant David Correa is in charge of Toronto Police’s human-trafficking enforcement unit. Cases concerning victims from Northern Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Canada routinely land on his desk. Most of them have been recruited by young men on social media, he says.

His job is to investigate the crimes but also to support the victims, who face enormous pressure to testify in court. Det. Sgt. Correa’s unit gathers evidence such as video surveillance to help support their cases. He says his unit will also help victims return to their home city or province.

Many victims are hauled across the country along the TransCanada and 401 highways, which are both notorious for sex trafficking. Ms. Drydyk says perpetrators stop at all the large urban centres along the way to make more profit. “They can use cars to travel really quickly between cities, and they can change their rental car in between those areas to avoid law enforcement detection,” she says.

Two other popular thoroughfares for traffickers are Ontario’s highways 11 and 17, used to move victims from Sudbury and Thunder Bay through Northern Ontario and onward to Winnipeg. Ms. Drydyk says they view the remoteness of these highways as yet another way to avoid the police.

All that moving around can certainly make it challenging to track their movements. “They’re gonna stay in a given hotel, probably a maximum of three days, before they start really bringing attention to themselves,” Det. Sgt. Correa says.

Police also face the challenge of getting victims to trust them. They can be reluctant to speak to police because they may have had a bad experience in the past, or their trafficker has forced them to commit fraud or recruit other girls.

/arc-goldfish-tgam-thumbnails.s3.amazonaws.com/02-22-2021/t_81eb32b7e2ad4c4f95adbe102287a59b_name_karly_church.jpg)

Karly Church is a human trafficking crisis-intervention counsellor who works with Victim Services of Durham Region and is embedded with Durham Police’s human trafficking unit. She’s also a survivor of sex trafficking who provides informal counselling and helps connect victims and survivors to services.

When police meet a victim, she often accompanies them to let them know she can help if they don’t want to talk to law enforcement. “I’d say every single time, the individual at least takes my phone number,” she says.

Sex trafficking doesn’t always involve moving victims around the country. A lot of Ms. Church’s younger clients were lured by traffickers at school. Sometimes it’s a fellow student or someone they met at a party or on social media.

“A lot of them who are under the age of 18, they go to school Monday to Friday, they come home after school, say they’re going to a friend’s house, and then they’re made to work by their trafficker.”

The centre’s report makes recommendations based on its findings, including investing in more interjurisdictional law enforcement teams and mandatory training for all levels of law enforcement. It urges finding ways to make the legal process less traumatizing for survivors, and encourages stronger partnerships between governments and organizations that work with survivors – as well as sectors used by traffickers, such as hotels and rental car companies.

“We implore all levels of government to work together on this issue and commit to funding anti-human-trafficking initiatives in perpetuity to ensure that programs and services can focus on what matters most: providing exceptional, meaningful and effective supports to victims and survivors,” the report reads.

How trafficking affects victims

Nova Scotia and Ontario have higher rates of human trafficking than the national average, with women and girls often lured by people close to them or over social media. Their traffickers then force them across the country. The Globe and Mail spoke with two women who shared their personal experiences being sex trafficked and a third woman who shares her daughter’s story.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/WOVTPUHS5JC43BZC6E2X46564E.JPG)

VANESSA TYNES-JASS

Vanessa Tynes-Jass was a 17-year-old straight-A student when she met the first man who trafficked her.

At the time – three decades ago – she was living in a rooming house in Dartmouth. A group of girls lived in the back of the house, and Ms. Tynes-Jass used to watch them put on makeup and go out at night. But she was busy with school and her job at McDonald’s, and didn’t think too much about what they were doing.

The girls started inviting her on shopping trips and to restaurants, telling her not to worry about paying because the owner of the house covered the bills. It turned out the man – who lived there with his family – was a pimp. After a few weeks of shopping trips, he told Ms. Tynes-Jass she couldn’t stay unless she did what the other girls did. She remembers asking, “What’s that?”

That night, she says, “they did me up and took me out, and I got turned out that night. So that’s the beginning of it.”

Over the course of 18 months, Ms. Tynes-Jass was trafficked by three different men and raped over and over again. She tried repeatedly to escape, but she wasn’t allowed to keep any money, and her pimps monitored her every move. She felt detached from her head and her heart, numbing herself to cope with the trauma.

The first time she hatched a plan to escape, her roommate went missing, so instead of making a run for it, Ms. Tynes-Jass went searching for her. The next morning, she heard on the radio that a body had been found in a garbage can. She went to the morgue and still remembers staring into her friend’s face.

That night, her pimp made her stand in the same spot her friend who was killed had worked the night before.

She was working up the courage to escape again when she was recruited by a group of girls who promised her their pimp would protect her. Instead, he put her in the backseat of a car and took her to Montreal.

Ms. Tynes-Jass’s anxiety swelled as they passed swaths of dense forest, taking her farther away from home. She knew of other girls who’d been taken and never returned.

“I had no say in the decision,” she says. “I had no say whatsoever.”

In desperation, she jumped out of the car before they reached Montreal and ran to a payphone to call police. But her freedom was fleeting.

She fell into the grips of a third man who sent her all over the country, making her stay with his family members or people he knew, so she was always watched.

“They would just trade girls,” Ms. Tynes-Jass says. “It’s like you’re a thing. You’re nothing to them. … They try to get you pregnant so you’re tied to them, so you can’t leave. You’re like a slave.”

After hiding enough money to buy her freedom, Ms. Tynes-Jass rented an apartment in Dartmouth. She remembers lying on the floor, thinking she was free. But the pimp and his friends found her and beat her so badly she thought she was going to die.

“They were kicking me in the head and the stomach, and I was telling myself, ‘You can’t pass out.’ They put me in a basement, and I got raped that night.”

She managed to escape again, taking a bus to herhometown of Truro. But when she arrived, the pimp was waiting for her in the parking lot. She refused to get off the bus until someone came to help – armed with a baseball bat.

After she was finally free for good, Ms. Tynes-Jass became pregnant and had a son. She returned to high school at the age of 20, secured a scholarship to Dalhousie University and went on to become a lawyer. She wanted to reach for a career that was beyond her wildest dreams, and strived to take care of her son.

She got married and started practising law in Halifax. But she was constantly reminded of what had happened to her in Nova Scotia. She now lives in Toronto with her family, where she runs a practice focused on family law and residential real estate. She also operates a charity called Survivors Unleashed International, which provides education funding to victims of trafficking.

Ms. Tynes-Jass says governments, schools and parents need to acknowledge the threat of sex trafficking and talk more about how girls are coerced.

“The real issue is these little girls are looking for love, and these pimps are exploiting that for their own greed and financial gain,” she says. “But they’re ruining lives in the process.”

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/APVTPQJTIZHARPK2J7OZ5HEJZI.JPG)

JENNIFER HOLLEMAN

Jennifer Holleman can never forget the moment she found out her 21-year-old daughter, Maddison Fraser, was dead.

It was July 8, 2015 – a Wednesday. Ms. Holleman and her then-partner were camping in Annapolis Royal, in western Nova Scotia. Her partner’s phone rang, and he quickly passed it to Ms. Holleman. It was her other daughter, who had grim news to deliver: Maddison, who had a three-year-old child, was riding in a vehicle with a man believed to have purchased her for sexual services. Around 2:15 a.m., the driver lost control and the car flipped, smashing into an apartment building. Both Maddison and the driver died.

“I just dropped in the trailer,” Ms. Holleman says.

Maddison was 19 when she moved to Grand Prairie, Alta., along with her baby and a friend her mother thought was a bad influence. Soon, Ms. Holleman started receiving photos sent by concerned friends – one of Maddison advertised on a website for sexual services, another of Maddison beaten so badly, her own mother didn’t recognize her. Ms. Holleman tried talking to her daughter, but the more questions she asked, the more Maddison pushed her away.

Ms. Holleman has since learned that Maddison was sex-trafficked across Alberta and Ontario for roughly two-and-a-half years before her death. In the time since, she has tried to piece together what happened to her girl. She knows her daughter’s perpetrators controlled her with violence and took away her ID. They even prevented Maddison from tending to her baby, and in May, 2013, Ms. Holleman travelled to Alberta to pick up her grandchild and bring her back to Nova Scotia.

“I don’t know how Maddison lived as long as she did,” Ms. Holleman says through tears. “That’s probably one of the hardest things for me to say. Because they just put her through hell.”

After Maddison’s death, Ms. Holleman went through her phone. It held what she thought was an important clue: a voice message her daughter sent to a friend, naming men who attacked her. On the recording, Maddison can be heard saying the men beat her badly, burned her with cigarettes and lit her hair on fire.

Maddison’s medical records – which Ms. Holleman fought to access – confirmed that and more: She had been raped multiple times, and had multiple contusions and bruised ribs. She’d had seven abortions in less than three years.

According to doctors’ notes, they asked Maddison if she wanted to contact the RCMP. She declined.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/RYV477QF6NPNRNMTJW4A6MKDPY.jpg)

The RCMP launched an investigation into the assault in August, 2015, a month after Maddison’s death. Corporal Deanna Fontaine, a media relations officer with Western Alberta District RCMP, told The Globe the investigation involved following up on information provided by Ms. Holleman.

By 2018, Cpl. Fontaine says the RCMP had exhausted all investigative avenues. Two reviews of the evidence concluded there were insufficient grounds to support charges, though she says the RCMP identified “a number of subjects of interest.” The investigation remains open.

Today Maddison’s daughter is 9, and though she now lives with her father, he and Ms. Holleman share joint custody.

“She’s going to have a happy life, and I don’t care what I have to do to make the majority of it roses and butterflies,” Ms. Holleman says. “That’s the way it’s going to be.”

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/LISLGROAP5ANDNL6NZX6QMRWXM.JPG)

CAROLINE PUGH-ROBERTS

Caroline Pugh-Roberts often wakes up to texts in the middle of the night from unknown numbers with the simple words: “I heard you could help me.”

Ms. Pugh-Roberts works at the Salvation Army in London, Ont., where she runs a program for people who have been, or are at risk of being, trafficked. That includes providing food and support and, most crucially, help escaping their abusers.

Drive by any hotel in London, according to Ms. Pugh-Roberts, and it’s likely someone is being forced to perform sex work there. “It’s that bad,” she says. The London Abused Women’s Centre says it provided support to 1,342 prostituted, trafficked and sexually exploited women and girls in its 2019–2020 fiscal year. Ms. Pugh-Roberts attributes London’s trafficking problem to its location along Ontario’s 401 highway.

Many of the victims who reach out for help find her through word of mouth, she says, “because … I have street cred, for lack of a better way of putting it.”

Ms. Pugh-Roberts was trafficked for eight years. She was 35 when she met her trafficker – her boyfriend – in London. She’d recently lost her husband, mother and two best friends, and she was vulnerable. He promised to take care of her.

But when they were confronted with being evicted from their apartment, her boyfriend turned on her, she says, and forced her into the sex trade. He told her she had to take care of “the family.”

He trafficked her in hotels, strip clubs, massage parlours and parks from Sarnia, Ont., to Toronto, with stops in cities and towns along the 401, including small centres like Princeton, outside of Woodstock.

Ms. Pugh-Roberts lived in and out of shelters before she was finally able to escape. She has never reported her perpetrators because they were associated with organized crime.

Now her mission is to help others. Ms. Pugh-Roberts says the victim stories she has heard through the pandemic have changed. She hears from a lot of girls – some as young as 12 – and increasingly they’re being trafficked by their families.

She points to one young woman in particular, whom she met this past spring at a local park. (It’s been harder to meet victims in relative privacy during COVID-19, with regular meeting places closed.)

The pair sat across from each other on a blanket. The 21-year-old victim had dark circles around her eyes and red marks on her neck, Ms. Pugh-Roberts says. “She was limp. Her body was just slumped. You could see the dejection, the hopelessness and the despondency. It was so visible.”

When speaking to victims, Ms. Pugh-Roberts says she never uses the term “trafficking” – that’s just not the kind of language victims use. Instead, she asked the young woman if someone was hurting her. The answer was yes – she told Ms. Pugh-Roberts her boyfriend was forcing her to perform sex acts both in person and via webcam.

During online sessions, he would stand on the sidelines, telling her what to do. When a purchaser told her to strangle herself with a tie, she pretended to pass out. Her boyfriend insisted she strangle herself until she was unconscious.

Ms. Pugh-Roberts says that young woman has not been able to escape her abuser.

She understands just how difficult it can be – it took Ms. Pugh-Roberts several attempts before she finally got away from her trafficker. “People say, ‘Why didn’t you leave?’” she says. “Oh, my god, there are so many barriers.”

What those people should be asking instead is why men continue to do this to women and what can be done to stop them.

“The onus is always on the victim,” she says. “It has to stop.”

FOLLOW JANICE DICKSON ON TWITTER @JANICEDICKSON